Continental philosophy is a set of 19th- and 20th-century philosophical traditions from mainland Europe.[1][2] This sense of the term originated among English-speaking philosophers in the second half of the 20th century, who used it to refer to a range of thinkers and traditions outside the analytic movement. Continental philosophy includes the following movements: German idealism, phenomenology, existentialism (and its antecedents, such as the thought of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche), hermeneutics, structuralism, post-structuralism, French feminism, psychoanalytic theory, and the critical theory of the Frankfurt School and related branches of Western Marxism.[3]

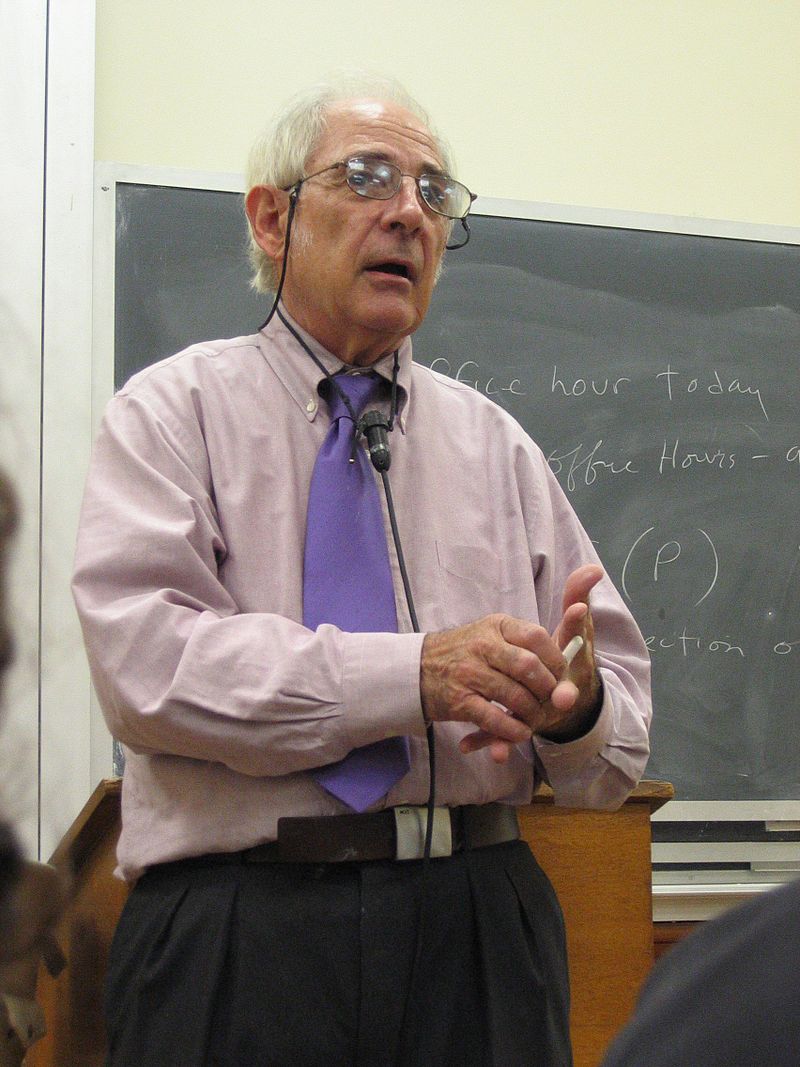

It is difficult to identify non-trivial claims that would be common to all the preceding philosophical movements. The term "continental philosophy", like "analytic philosophy", lacks clear definition and may mark merely a family resemblance across disparate philosophical views. Simon Glendinning has suggested that the term was originally more pejorative than descriptive, functioning as a label for types of western philosophy rejected or disliked by analytic philosophers.[4] Nonetheless, Michael E. Rosen has ventured to identify common themes that typically characterize continental philosophy.[5]

- First, continental philosophers generally reject the view that the natural sciences are the only or most accurate way of understanding natural phenomena. This contrasts with many analytic philosophers who consider their inquiries as continuous with, or subordinate to, those of the natural sciences. Continental philosophers often argue that science depends upon a "pre-theoretical substrate of experience" (a version of Kantian conditions of possible experience or the phenomenological "lifeworld") and that scientific methods are inadequate to fully understand such conditions of intelligibility.[6]

- Second, continental philosophy usually considers these conditions of possible experience as variable: determined at least partly by factors such as context, space and time, language, culture, or history. Thus continental philosophy tends toward historicism (or historicity). Where analytic philosophy tends to treat philosophy in terms of discrete problems, capable of being analyzed apart from their historical origins (much as scientists consider the history of science inessential to scientific inquiry), continental philosophy typically suggests that "philosophical argument cannot be divorced from the textual and contextual conditions of its historical emergence".[7]

- Third, continental philosophy typically holds that human agency can change these conditions of possible experience: "if human experience is a contingent creation, then it can be recreated in other ways".[8] Thus continental philosophers tend to take a strong interest in the unity of theory and practice, and often see their philosophical inquiries as closely related to personal, moral, or political transformation. This tendency is very clear in the Marxist tradition ("philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it"), but is also central in existentialism and post-structuralism.

- A final characteristic trait of continental philosophy is an emphasis on metaphilosophy. In the wake of the development and success of the natural sciences, continental philosophers have often sought to redefine the method and nature of philosophy.[9] In some cases (such as German idealism or phenomenology), this manifests as a renovation of the traditional view that philosophy is the first, foundational, a priori science. In other cases (such as hermeneutics, critical theory, or structuralism), it is held that philosophy investigates a domain that is irreducibly cultural or practical. and some continental philosophers (such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, the later Heidegger, or Derrida) doubt whether any conception of philosophy can coherently achieve its stated goals.

Ultimately, the foregoing themes derive from a broadly Kantian thesis that knowledge, experience, and reality are bound and shaped by conditions best understood through philosophical reflection rather than exclusively empirical inquiry.[10]

-

- Leiter 2007, p. 2: "As a first approximation, we might say that philosophy in Continental Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is best understood as a connected weave of traditions, some of which overlap, but no one of which dominates all the others."

-

- Critchley, Simon (1998), "Introduction: what is continental philosophy?", in Critchley, Simon; Schroder, William, A Companion to Continental Philosophy, Blackwell Companions to Philosophy, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, p. 4.

-

- The above list includes only those movements common to both lists compiled by Critchley 2001, p. 13 and Glendinning 2006, pp. 58–65

-

- Glendinning 2006, p. 12.

-

- The following list of four traits is adapted from Rosen, Michael, "Continental Philosophy from Hegel", in Grayling,

-

-

- محمودرضا قاسمی A.C., Philosophy 2: Further through the Subject, p. 665

-